Patreon’s Struggle with Subscriptions

Hello, I want to say thank you to everyone who helped me on the hunt for a new job. Last month, I took a job for a New York City public agency – far, far away from music. This won’t immediately impact my work here but please do be patient if I’m a bit slow to respond to emails throughout the rest of the year. The other bit of news for you readers is that I’m doing another reader survey that can be completed here. (It should take less than 5 minutes to complete; I'd really appreciate your feedback so we can continue to improve this newsletter.) Lastly, if you want to support the newsletter, please recommend it to a friend or subscribe here. Now, let’s look at Patreon.

Money 4 Nothing, Brooklyn’s favorite podcast about music and capitalism, covered the recent layoffs at Bandcamp with me loudly on the mic giving some additional commentary. Sam and Saxon also looked at the recent disastrous New York City Electric Zoo concert and what it portends about contemporary nightlife culture Check their newsletter here.

The word of the year for certain pockets of the music industry appears to be “Superfans”. Simply put, the flat nature of music streaming revenue obscures how much an individual music consumer might potentially spend. This spawned a renewed interest in getting fans to spend more money beyond passive streaming platform subscriptions. An understandable business concern, as the industry sees slowing streaming growth, increased pressure to raise prices, and a need to adjust the overall streaming payout model. Yet, if the issue with streaming is that everyone is paying the same, which makes it hard to reward artists with more dedicated fans, perhaps all that’s needed is a different kind of subscription model.

The irony is that the industry already did this hype cycle a few years ago with seemingly zero interest in learning any potential lessons. This month I want to look at Patreon and Twitch, which both offer similar products to any number of emergent startups and business practices catering towards “superfans” but at a much larger scale. And yet despite the leg-up, both platforms have seen declining growth, creator fatigue, and an inability to adapt to a post-pandemic environment.

Before diving into Patreon, I’d like to share a little more background context. Back in 2008, Kevin Kelly wrote a blog post called ‘1,000 True Fans’ that argued artists didn’t need the scale offered by major labels, publishers, etc. but rather just needed one thousand fans who’d be willing to support their work. At first glance, it sounded pretty reasonable since most artists know a million people would never buy their album or will ever play to a 70,000-seat arena. Yet one thousand people watching them perform a show, while impressive, didn’t feel at a scale that is incomprehensible.

The essay notably predated Kickstarter, IndieGoGo, Bandcamp, Patreon, etc., but simply reframed conscious consumer ideology with a bit of techno-utopianism. (One can both be a good consumer but no longer bound by the options in the physical world.) Where before an artist may have only gotten fifteen fans in their hometown, the internet can now potentially extend the artist’s reach without them having to compromise on their artistic vision. This model is in many ways not too distant from small press publishing but it’s connected with the internet’s sense of scale that would provide the illusion of more opportunity available to aspiring creatives. Suddenly everyone with internet access was being told the people who’d support them to sustain their own unique artistic careers were just a few clicks or swipes away.

The idea would be discussed and critiqued over the years. Li Jin, a venture capitalist who backed Patreon, wrote about ‘100 True Fans’ upping the anti of telling creators to seek out high-paying patrons, so one didn’t even need 1,000 fans. But even that proposal began to show some signs of cracks. If the issue with one thousand true fans is that it’s still too many, then how does reducing the number of fans but increasing the revenue-per-fan help artists who don’t make works desirable for extremely deep-pocketed listeners? Thus, it shouldn’t be a surprise Jin jumped fully into Web3 and crypto during the pandemic, as it simply amplified the thesis that she and her peers were pushing. If the future supports creative works through the power of new internet-enabled technologies, then let’s now dive into Patreon, since after all, it was a musician/YouTuber who founded the crowdraising platform.

Pumping the Patreon Bubble

The origin story of Patreon is easy to love. Co-founded by Jack Conte of the popular YouTube act Pomplamoose, he was inspired to create the platform because of what he saw as the busted economics of producing content for YouTube. Basically, his videos would receive millions of views but barely made enough to justify the initial costs. Thus, Patreon offered a way for his audience to directly support his work without him having to rely solely on YouTube advertising revenue. Readers of this newsletter might quickly remember the years of complaints musicians and labels have held towards YouTube, then Spotify, and now TikTok wound up in that narrative. Yet, to be clear, YouTube in the mid-2010s wasn’t profitable, and while Google was certainly spending on lavish office campuses and high executive and employee compensation, it’s not clear how much any creator on the platform should’ve expected to make from ads slotted between videos of bears falling on ice and old Miley Cyrus songs.

The assumed desire that YouTube should be able to pay a reasonable wage to all successful creators does in many ways run counter to what at that point was still just a platform for everyday people to upload videos for fun. That initial use case of the platform, as a privatized video library, doesn’t immediately align towards supporting full-time or even part-time creators. A decade later it’s easier to critique Conte’s line in the sand drawn between one form of revenue (advertising) and another (paid subscriptions) but the romanticization of crowd-funding to the detriment of all other forms of monetization would quickly start to unravel. If Patreon’s entire business model is to take a small percentage of each subscription, then as a company it needs a lot of creators, but perhaps more importantly, it also needs high-paying customers to maintain its operations and justify the millions of dollars of investment.

The cracks in Patreon’s image started to form when the company promised some changes to the creator tiers in an effort to increase that percentage take. This was met by swift creator pushback and the company backtracked on implementing these changes. Yet this was a clear warning sign that the company needed to make some real changes to its economic model. YouTuber Tom Nicholas in his video ‘The Rise (and Fall) of Patreon’ walks through each announcement the company made about trying to slowly take a bit more money from creators by upsetting their user base too much. Though they did eventually roll out these changes, the company appeared ready to try and find a new way to spin its new direction…bring on the musicians.

What Goes Up…Must Go Down

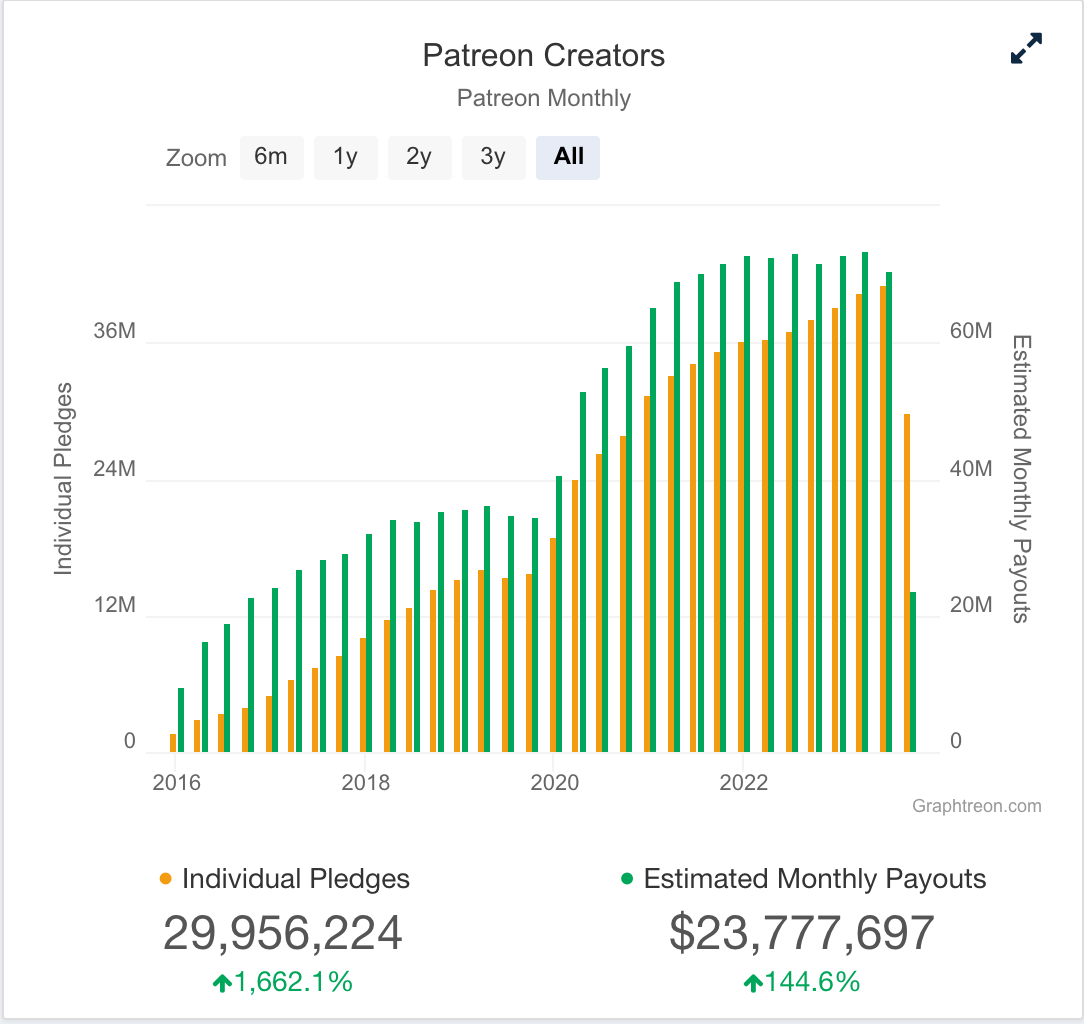

The company championed the investment of Serj Takian, of System of the Down, fame. They pumped out press releases around M.I.A. beginning to use the platform. Suddenly looking for a new market beyond podcasters and YouTubers, Patreon went back to its roots. However, while the world suffered with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Patreon, like many tech firms, saw a massive spike in users (see the chart below).

Even still, prior to the jump in users, Patreon kicked off the pandemic making a 13% cut to staff, a sign not only of the economic uncertainty but also of the precarious state of the company. Patreon was already trying to figure out ways to inch up how much money it was taking from creators, so the initial shock of the pandemic must’ve been a cause for great alarm. Yet by the summer, Patreon was seeing a massive spike in the number of creators and supporters. That growth continued, though at a slower pace, until early 2022. It was during this moment that the company leaned on musicians again, brought on Joe Budden, the rapper behind one of Spotify’s early big podcast bets, and was all in the creator economy thesis. (Li Jin mentioned earlier is also one of the venture capitalist backers of the company.) The financial worries of the company were forgotten as the company was able to raise $155 million in the spring of 2021, putting its valuation at $4 billion. Now, a company that only two years prior was already starting to show financial instability just raised nine figures without any significant changes to its business model. It’s not hard to imagine what happened next.

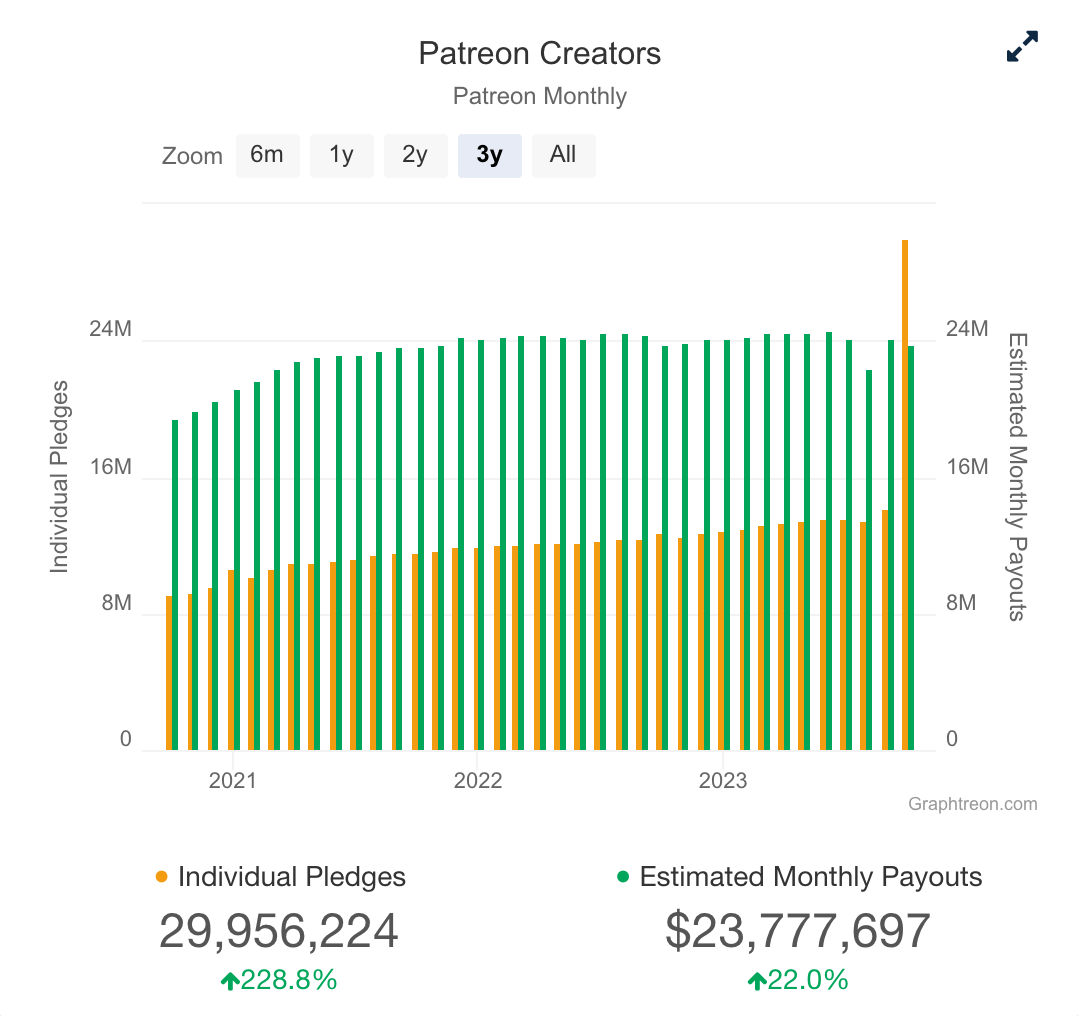

That pandemic-era growth the company enjoyed topped out by the summer of 2022 with 2023 representing a bit of a backslide in terms of revenue. That could account for the 17% cuts that the company made last September and a string of bad press about it being a poorly run business. The Information reported that the company saw its valuation fall by 70%, and recent partnerships with Spotify, the acquisition of fledgling startups, and the rolling out of more commerce features would show the company is desperate to find something to reverse its stagnant user base. The end of the pandemic left Patreon back where it was at the end of 2019, with a stagnant user base but also with an even more inflated trunk of venture capitalist expectations and dollars.

Nearly three years ago in that covid-era high, Jack Conte told Billboard: “Every artist, every creator in the world is going to have a membership line of business — just like they have a touring line of business and a merch line. Creators are very much realizing the importance of diversifying their incomes.” I don’t look to challenge the importance of diversification because it’s a good tactic for any business to take. However, the economics of pure subscriptions just don’t make sense at this point. Patreon raised hundreds of millions of dollars with no clear path forward toward an IPO, especially considering the relative flops of recent efforts and declining engagement from users. Yet, as the music industry eyes “superfans” and the exploitative tactics used by mobile games and K-pop, there are clear limits to how much one can squeeze out of fans before they simply take back their credit cards.

Unheard Labor

Workers across seven venues in Minneapolis with First Avenue Productions are unionizing with United Here Local 17 and already received voluntary recognition. The Society of Authors in the United Kingdom is speaking out against major book publishers for their Spotify deal to offer audiobooks on their platform without accounting for authors. Even if Spotify’s not facing their immediate ire, this would show that audiobooks, beyond still being completely unproven business-wise, might not be less complicated than the licensing concerns regarding music. The ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike is now the longest in the union’s history, but negotiations are ongoing with proposals being traded across both sides. Then in broader labor news, the United Auto Workers reached tentative deals with Ford, GM, and Stellantis that are currently being voted on by members, but early commentary sees this as a historic win for the union.

In the bummer section. Last month, BMG announced layoffs of 40 employees in a company “reorganization”. Techstars, a six-year-old music tech incubator revealed it was shutting down, which harmonious with Ampled, a music co-op I was on the board of, also announcing its demise. Despite there being much hype around music NFTs a couple of years ago and now millions flooding into the AI space; there isn't a clear direction for the next piece of notable music technology. There’s also the underrated reality that most of these startups can best hope to be absorbed by a larger firm (a major label, DSP, or Live Nation) since they’re the main power brokers within these markets.

Government Tunes

Governments around the world appear to be taking the arrival of commercial artificial intelligence far more seriously than a number of other recent technologies. Now that mostly means asking for public-private collaboration, light government oversight, and pledging to support copyrights. All of this is sure to be welcome news for the music industry, which is ever more reliant on lording copyrights over any prospective money source. Not really music related but a number of attorney generals across the country sued Meta over the potential mental health harm of its products on young people. Sue ‘em, ban ‘em, social media usage reduction is always welcome news.

A Note of Financialization

Warner Chappell Brazil picked up the catalog of the publisher Deck. Graham Nash sold unreported parts of his catalog to Iconic Artists Group, similarly mysterious is where IAG raised the capital for its purchases over the past few years, in case any readers hold further insight. Still spending down the $1 billion raised from Apollo Global Management, Harbourview picked up the catalogs of Christine McVie, Pat Benatar, Neil Giraldo, and “select publishing assets” from Kane Brown. Speaking of large sums of money, CTM Outlander, who raised a billion back in 2021 from Outlander Fund; CTM BV, bought the catalog of Ross Copperman. BMG picked up the catalog of French electronic producer Martin Solveig. Last, Peermusic bought Arctic Rights Management, a large Norwegian publisher, continuing their years of multi-national acquisitions.

Last year, the private equity firm Francisco Partners bought 90% of Kobalt Music Group for a reportedly little over a billion dollars. Curiously, last week it was announced Morgan Stanley Tactical Value is partnering with Kobalt to potentially invest $700 million into music copyrights in the coming years. The vagueness of this press release is curious considering Kobalt already sold off a couple of song rights investment funds in 2020 and 2022. Either way, the capital merry-go-round continues, allegedly. O, Anghami is hurtling fast towards a delisting from the Nasdaq; no one could’ve seen that coming.

Where to begin, where to begin. Last month, Hipgnosis Song Fund shareholders held two votes about the future of the company. By an 83% margin, they told Merck Mercuriadis to reorganize or potentially shut down the company; they also shot down an attempt to sell some of the Fund’s assets to Hipgnosis’s Blackstone-backed fund. Only a couple of weeks prior, Hipgnosis was forced to walk back a shareholder dividend payout, because it miscalculated expected payments. Yesterday they announced two fellas who were leading the Round Hill Music Fund, which similarly floundered on the public market, are stepping up for Hipgnosis. Perhaps the very public owner of the fund will find a way out of this mess but it’s hard not to see this as a continued slow unwinding of a low interest rate, pandemic-era bubble.

6 Links 2 Read

Twitch, YouTube Are Slowing Big-Money Deals for Gaming Talent - Bloomberg / Twitch Just Changed Livestreaming FOREVER → SIMULCASTING - Devin Nash

Twitch is moving away from dropping cash on streaming deals and is allowing all streamers to broadcast across more platforms without facing consequences from the Amazon-owned company. Devin Nash’s video is great in explaining why Twitch made this decision but I’m more skeptical about the prospects of livestreaming’s future. It’s still one of the most expensive and labor-intensive forms of digital media creation and it’s still not clear to me how sustainable a model it is for most creators.

Spotify Plots Change to Royalties Structure, With a Minimum Streams per Song Requirement for Payout - Pitchfork

Spotify’s proposed royalty changes are fine. Truthfully, the fact Ek was so publicly dismissive of doing such a thing even just a few months ago is a bit annoying to see such a 180. However, now that they’ve moved here and begun implementing price increases, the industry’s new terrain is set. Streaming will cost more and explaining how your favorite artist gets paid will get more not less complicated. They’ll likely get a few more dimes every paycheck but it's hard to see that as “victory” in the eyes of major rights holders.

Spotify Is Eating the Entire Music Business - New York Magazine

Always nice to read mainstream music streaming coverage that holds a critical eye towards the business. This echoes a recent Eamonn Forde op-ed where people understand the permanence of Spotify in today’s music ecosystem and are urging to identify the company’s overreach as not being good for its health, or potentially the rest of the industry.

The Big Business of Stan Culture - The Exiled Fan

Monia continues to explore the economic impacts of “stan” culture. Taylor Swift, the example taken here, with sky-high tour ticket prices, the endless repackaging of her albums to juice the charts, and even a cash-grab concert film represents further exploitation of desperate, wealthy fans rather than a model of “old school” music industry success. There’s a reason K-pop is so often cited by critics of fandom because it, like Taylor Swift, represents manufactured pop music with a real budget and vision, which often lacks, and decayed, in other music genres.

Is Pop Music Stuck in Place? - The New York Times

A great conversation about why it appears there are only eight pop stars in the world and why it feels so difficult to produce new ones in 2023.

“K-Pop Studies” is a joke - The Idolcast

Sadly, though not surprising, decades of degrading academic institutions and obsessive fan behavior are producing a flood of low-quality K-pop research.