The Record Industry Can’t Fit in a Smart Speaker

Hello, hello! Penny Fractions returns for a new month of commentary, criticism, and cross-talk about the record business. I haven’t said this in a minute but if you’re a new $3 Patreon subscriber, please let me know so that I can mail you logo stickers! And if you’re a new reader, do check out my previous newsletters. Otherwise, let’s get to talking about smart speakers!

The Hype Around Voice

Over the last few years, there’s been quite a bit of attention around voice assistance, smart speakers, or whatever term one prefers for always-on, internet-connected microphones. Whether talking about Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, or Google Home products, around every holiday season there’s a new rush to talk about the adoption of these devices. Ben Thompson at Stratechery captured this in early 2017 in his article titled “Alexa: Amazon’s Operating System”, where he speculated whether voice might be tech’s next major frontier after Windows, the iPhone, and Facebook/Google. The observation about Amazon’s potential dominance in this space held up, as the price of Alexa devices fell, sales continued to climb, while Google saw a decline in sales for their own smart speakers.

Projected sales of smart speakers, in the United States, are predicted to increase but are already seeing signs of stagnating growth, as most people already have a smart speaker: their phones. In 2018, when writing “The Battle for Home”, Thompson admitted that voice, as it turns out, might not quite be the next great technological shift as the smartphone:

What made the smartphone more important than the PC was the fact they were with you all the time. Sure, we spend a lot of time at home, but we also spend time outside (AR?), entertaining ourselves (TV and VR), or on the go (self-driving cars); the one constant is the smartphone, and we may never see anything the scale of the smartphone wars again.

I can’t say I wasn’t immune to the hype around voice a couple of years ago. The technocentric mindset of always wanting to see every new piece of technology made obsolete and pivot an entire industry is a part of what’s sustained capital within the tech industry over the last fifteen years. (Also, what sustains the lives of people who professionally write about tech!) If every startup can’t change the world, why invest money or word count? Now, within the context of music, Thompson’s comparison between the smartphone and the speaker is fairly salient. All of the attention around smart speakers and music seemingly ignores the fact the primary mode of music consumption for many people is already a “smart speaker”.

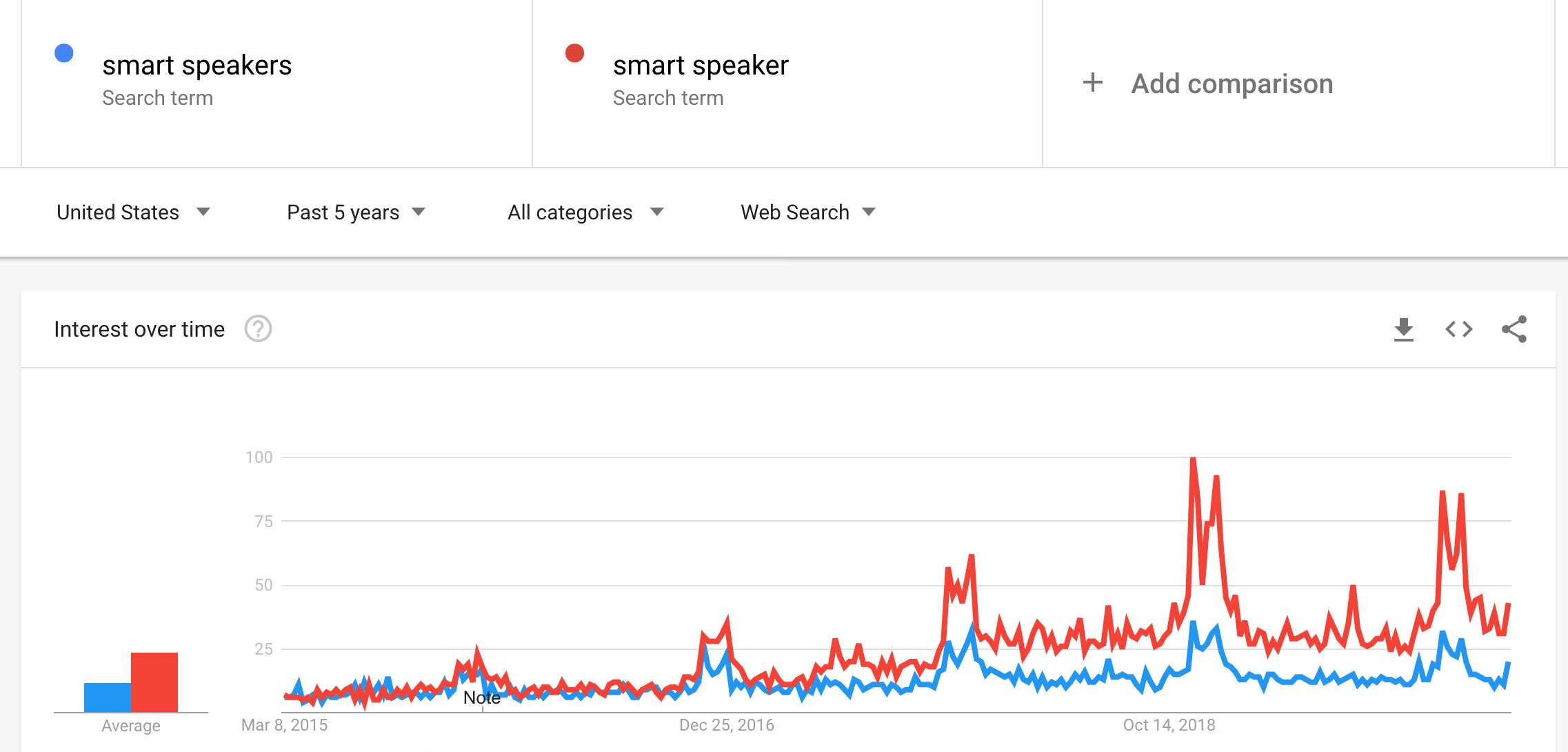

This might give a slight explanation of why 'voice' peaked in Google search terms in 2018, but over the last five years there’s been little change to how people interact with music, even on smartphones.

A theme I keep returning to over the last few months is this sense of stagnation happening within the music industry as it sees a return to extreme growth. That’s why I wanted to return to voice this week; something that only a couple of years ago felt important and now feels almost worth forgetting.

How To Fake a Hit

This shouldn’t be all doom and gloom for voice. That’s because you (yes, you) can indeed leverage the power of technology to get a number one song. That’s what Amazon did last year for Ellie Goulding, where if someone in the United Kingdom requested Christmas music from Alexa, they’d eventually be served Ellie Goulding’s cover of Joni Mitchell’s “River”. This was done enough times over the holidays to become the last number one song in the 2010s in the UK. Essentially, an advertisement was able to game the charts and sit up at the top (Not unlike what’s happened on YouTube). Music industry analyst Mark Mulligan wrote a bit on the song’s rise last year (emphasis mine):

Just like with radio, lean-back listeners are unlikely to stop whatever else they are doing in order to change the track. Because streaming economics do not differentiate with lean-back and lean-forward listening, passive listening is just as valuable as active listening. Radio has become as valuable as retail but is much easier to manipulate.

What strikes me about this vision of corporatized music that Mulligan describes is how absurdly out of reach it is for any aspiring artist. The idea of success here isn’t getting to open for a beloved band, hearing one’s self on the radio, or even seeing one’s record at a store. Or even being able to make a decent living. Rather, it’s that one is able to produce music mundane enough to be shoved into the audio stockings of passive music listeners that may enjoy your art but, ultimately, all that matters is that it was artificially jammed into enough playlists to find success. The absurdity of this promotion makes one ask a bit deeper a question: What is the value of voice in the current record industry?

Is There Any There, There?

Last fall, Spotify started a campaign of thurling Google Home Minis at premium subscribers. A successful product is usually one that needs to be bundled with a competitor’s streaming platform. Instead, there is already a push to rethink where the best use of voice might be if it isn't in a home recording box. A report last month pointed out that voice assistance was making more inroads within cars than homes. There is also still the increased skepticism towards smart speakers with reports of Amazon workers listening in on conversations that consumers did not know were being recorded.

This is what I found so remarkable about the story of Elle Goulding’s late December hit. That form of manufacturing success is a slight admission that voice is not offering a lot of new ways of thinking about the record business. Much in the same way that every successive story about TikTok continues to just build upon the same playbook of YouTube/Vine, voice so far has failed to offer a new roadmap beyond opening the pocketbook for advertising. The novelty of a screenless experience for interacting with music mediated through Amazon and Google isn’t offering any real novelty. Rather it remains a testing ground to benefit music’s elites, who can afford, whether with real dollars or corporate weight, to experiment. In other words, Joni Mitchell covers for some, and Baby Shark for others. And for artists outside of those conference rooms, another lane closed.

Unheard Labor

Only a couple of months ago I wrote about Patreon and what it could be doing for musicians, and much like a wish upon a monkey’s paw, the company appeared to listen. First was the announcement of M.I.A. hopping on the platform, which I gotta give a shout to Liz Ryerson for analogizing this to Apple’s deep history of vampiring the cool of music into its own product. Yet, the more troubling news was that Patreon was going to start handing out tiny loans to aspiring creators, which a tweet called “financialization” and what I’d call a clear sign of desperation. On the music side, Stem, an L.A. based-distributor, is dipping into the world of advances, which indicates that the record industry’s attachment to the tech capital is continuing to reap rewards.

Also in the realm of financialization, Resident Advisor announced a deal with Spotify to help promote live events for artists. The actual details of the deal are in a way fairly bland but speak to a fact written in an essay by DeForrest Brown Jr. about RA’s own infiltration into the “underground” electronic music scene. That over the last decade-plus the website’s gotten more enmeshed into a culture in a way that centralizes itself over the many communities it covers and promotes. In general, I hold skepticism towards these kinds of partnerships to bare out real results but one shouldn't hold back criticism of RA partnering with a company that in many ways presents music in a manner that is entirely antithetical to how most musicians they cover would like to be contextualized. Hopefully, it was worth the press releases and incomprehensible data.

Last quick note, here is a short story about musicians and the recent AB5 law that was passed in California and the various sides of the discussion around whether it’ll help or hurt musicians. My broad view on AB5 and similar legislation that are supposed to help American workers is that it’s certainly worth striving to improve such laws but that outright attack pro-worker legislation only further atomizes workers from pointing their ire at controllers of capital, not their peers.

6 Links 2 Read

Spotify’s Newest Pitch to Labels and Musicians: Now You Pay Us - Bloomberg

Small rant here: Business reporting exists to center the biggest players, which often obscures the real potential effects of business changes. Spotify reportedly asking labels to pay for on-platform advertising is certainly going to annoy major labels and scare independent labels, who know they’ll likely be screwed by the practice. Yet, this repeats a similar trend to Facebook nearly a decade ago, when the company suddenly demanded payments to reach the audiences that bands, labels, venues, etc built. What was once a way to connect was suddenly just another expense. Ultimately, major labels hold the power to negotiate better deals from this type of program and left in its wake will be no semblance of a music platform for artists but simply another marketing tool, where your fans listen to music with a bill attached underneath.

What Is Password Sharing Costing Streaming & the Music Business at Large? - Billboard

Last year, when I wrote about the RIAA’s attempts to sue fans for file-sharing dating pre-Napster, part of the reason is that the goal of these efforts isn’t really to “help” the industry but rather to justify the existence of such groups and cover industry struggles. Now this story about the “costs” of password sharing is purely fear-mongering, especially when the alleged amount is $300 million, which is 4% of the record industry’s 2019 revenue, and this assumes that the 11 million people who share passwords aren’t paying the standard $9.99 for a streaming service and not one of the many, many lower discounted rates available, or simply might be a non-paying user.

Bootleg Podcasts Are a New Frontier for Unlicensed Music on Spotify - Pitchfork

I love discovering the many ways that people discover loopholes within platforms. Part of the joy is seeing the cracks within the latest forms of platform capitalism but also to help understand how what is considered “bootleg” today will rapidly become part of the norm.

The TikTok-Ready Sounds of Beach Bunny - The New York Times

This is a fun little profile of an indie band that happened to land on a TikTok hit. Another great exception proving the rule of TikTok success!

Music-streaming services are losing their brand identity. Here's the visual evidence - Cherie Hu

I’ve complained and hold no desire to let up about the flatness of music streaming platforms. Still, Cherie Hu’s side-by-side of the major music streaming apps really just shows how all of these companies have effectively given up trying to create a unique product in this space. Competition is working great here folks.

An Oral History of ASMR - Rolling Stone

I don’t know a ton about ASMR but I found this a great read to dive into the history of this community and the ways it fought YouTube and pressures of commodification as it has grown this last decade.