Why Not Fake Your YouTube Views?

Hello, readers new and old to another exciting edition of Penny Fractions. Gonna keep it old school and say that if you want to support this newsletter, check out my Patreon page (I have stickers!) or simply recommend your favorite issue to a coworker, friend, or sentient creature from the local swamp. Also, if you ever want to contact me, simply reach out at pennyfractions@gmail.com! Otherwise let’s chat about YouTube numbers, press strategies, and media spins.

Last month, Bloomberg reported on how the YouTube record for the most views within 24 hours was broken but being quietly unacknowledged. The Indian rapper Badshah got over 75 million views with his song “Paagal”, just edging over K-Pop icons BTS’s own song “Boy With Luv”, which hit 74.6 million earlier this year. The article points out that industry sources accused Sony Music, Badshah’s record label, of using bot farms to inflate the number of views and alleged that’s why YouTube held back crowning a new record holder. The brief story contained what I thought was a rather revealing couple of sentences highlighting the specific methods and actors within the space of falsifying YouTube numbers:

When releasing a new single, major record labels will buy an advertisement on YouTube that places their music video in between other clips. If viewers watch the ad for more than a few seconds, YouTube counts that as a view, boosting the overall total. Blackpink and Swift, among others, have done it. Badshah just took it a step further, people familiar with the matter say.

The rather bold accusation that two of the world’s biggest pop stars inflated their own YouTube numbers snuck into this piece without any second thought. Even the phrase “among others” is doing quite a bit of power-lifting to cover for however many artists of a similar tier might also be inflating their YouTube numbers. Yet, the banality of such number manipulation speaks to the question of who is really the audience for these eye-popping numbers: Advertisers.

In this case, the method of manipulating YouTube views isn’t simply getting a bot to refresh a video, as was the case back in the late 2000s. Instead, labels bought advertisements for the explicit purpose of using a bot farm to produce fraudulent views. The self-contained loop is one that YouTube (without any government regulation of its platform) can pick-and-choose when to legislate, as The New York Times reported last year.

Last year, I wrote about my issue with Spotify’s Monthly Listener metric that essentially just exists to inflate the perceived popularity of an artist: “Now I took the bait and saw that Bryan Mg only has 895 followers on Spotify, while his current monthly listeners are over 160,000. Imagine trying to book a show saying you have less than 900 followers [or] 160,000 Monthly Listeners?” Where Spotify’s faulty metrics skew the perception of artist popularity across the spectrum of popularity, YouTube views pioneered the digital method of generating preposterous numbers to craft media narratives for music's most popular acts.

Numbers Keep on Spinning and Spinning

In early 2008, “Music Is My Hot Hot Sex” by the band CSS, amassed millions of plays and eventually overtook the video “Evolution of Dance” to become YouTube’s most-watched video. The only issue is that the views for CSS’s song were allegedly faked. Andy Baio, a blogger at the time, crunched the numbers and revealed that the comments and likes on the video appeared out of synch with similarly popular videos, which lead to YouTube investigating the validity of the views. The company never made an official proclamation either way but the original fan-made video for “Music Is My Hot Hot Hot Sex” was eventually deleted from the platform. However strange that moment was, it helped establish what would quickly become the norm regarding YouTube views.

A few months later in July 2008, Avril Lavigne's single “Girlfriend” became the most-viewed video on YouTube, surpassing “Evolution of Dance”. However, another controversy arose. Wired reported on a forum admin from a Lavigne fansite telling fans to use a YouTube auto refresher to goose the number of views on Lavigne's video. (Note: This was a point where a YouTube video was simply a page hit not indicative of actual video consumption.) No one from YouTube or her record label commented on the story and the fansite denied that such tactics were used. Even still, the two incidents helped establish that without there being an incentive or public pressure to change its system, YouTube was fair game to be manipulated for a quick press cycle.

Vevo’s Neverending Record-Breaking Debuts

Launched in 2009, Vevo was an attempt by Universal Music Group and Sony Music to create a better platform for attracting advertisers (initial partners included: AT&T, Colgate, and McDonald's) to their platform than solely relying on YouTube. Sounds familiar. This wasn’t a terrible idea, except for the fact that a major source of music consumption continued to happen on YouTube, not Vevo. Thus, in early 2012, the music-consuming public was introduced to the Vevo Record, an effort to create hype around music video debuts on the platform. The first to gain attention was Nicki Minaj’s “Stupid Hoe” with 4.8 million views in January 2012.

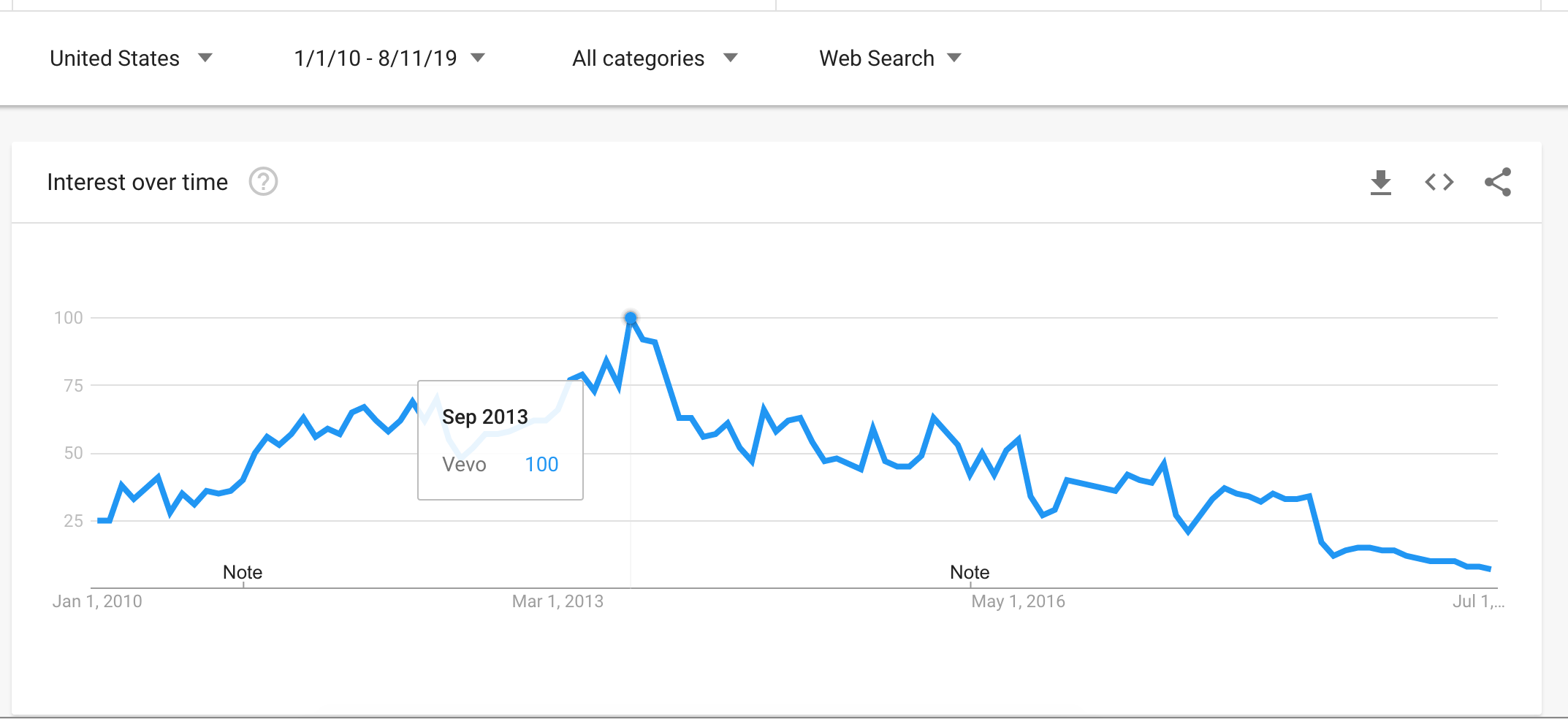

I’d like to throw scare quotes around this particular “honor”. The only purpose it served was to build attention towards Vevo, not YouTube. Vevo did see increased press but, unlike the late 2000s, viral YouTube moments like Rebecca Black’s “Friday”, the major label-backed company only served a single class of artists. The attention went towards the Rihannas, One Directions, and Adeles establishing that only pop’s most established stars could benefit from such numbers jockeying. A glance at Google Trends shows that searches for Vevo peaked around September 2013 around the release of Miley Cyrus’s “Wrecking Ball”, perhaps one of the most try-hard attempts at virality in this decade.

Numbers For Advertisers, Not Musicians

In the last few years, the attention around record-breaking YouTube debuts is an honor that is squarely centered around K-Pop stars like BTS and BlackPink who, according to Bloomberg, allegedly also inflated their YouTube numbers. Even if fans latch on these numbers and come up with schemes to boost up the views of their favorite acts (YouTube comments of a K-Pop song do this in real-time), this is ultimately just a vanity metric to point out how much advertising can run against music videos. Certainly, a video's number of views can establish baseline popularity but it should offer a, not the only, signal.

That’s why the creation of Vevo stemmed from a feeling that music videos, a large driver of YouTube video consumption, especially at that point, weren’t being given proper advertising funding. When over one billion people use YouTube and only 15 million are paying for it ad-free, then knowing a major pop star might get 40 to 50 million streams in 24 hours is thrilling news for anyone wanting to get a product in front of a young impressionable audience. Even if the numbers are faked, unless someone is willing to call out YouTube, all that matters is those potential ad impressions. So, truly, fake it till you make it!

Unheard Labor

Corey Taylor of Slipknot criticized music streaming services for appealing the recent Copyright Royalty Board ruling to increase pay for songwriters. His tweet did imply that artists aren’t paid at all, which is isn’t quite correct, but you know, H20 lean the same thing. I admire the bluntness of the critique. Tomorrow is the deadline for the Distinguished Concerts International New York musicians to vote on joining Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians. Obviously, good luck to all those who are hopefully voting #unionyes.

6 Links 2 Read

Want to Get on the Radio? Have $50,000? - Rolling Stone

Payola? In 2019? In the music industry? I’m shocked! However, the government’s history of regulating radio broadcast does make me want to imagine what it’d look like for a deep government investigation into how radio and digital music promotion work. Personally, I would love to see it.

Alternative financing for independent artists: An overview of emerging models in recorded music - Water and Music

Cherie Hu really dives deep into recent history tracking the number of companies attempting or have attempted to change the funding model for independent artists. Many of these ideas appear to be fledgling or undercooked, but I’m always pro outside the box thinking in regards to reimagining the music industry, so godspeed to everyone trying to make this space work!

The major labels are close to generating $1m from streaming every hour – but global growth is actually slowing down - Music Business Worldwide

No one appears to care about the slowing growth of music streaming, which is perfectly fine. I’ll just keep mentioning these articles until people start collectively freaking out in 2021.

Copyrighting the 'Building Blocks' of Music? Why the Katy Perry Case Alarms Producers - KQED

I do hold an out there belief that copyright, especially in the context of music, is a horribly outdated context that only helps the most litigious creatives (or their representatives). This most recent example against Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse” only further established what was clear: this was not plagiarism but rather two artists using similar chords, because there are only so many chord progressions in existence.

A user-centric streaming model could save the music industry - SoundCharts

I’ll continue to hold skepticism towards the user-centric streaming model but I found Damon Krukowski’s idea around copyright-free streaming a far more noteworthy prospect.

9128 is a streaming service focused on ambient/electronic music - Music Ally

Smaller label-specific streaming services/radio is something I find really interesting, so I wanted to check out what 9128 is doing here.

The Penny Fractions newsletter arrives every Wednesday morning (EST). If you’d like to support it, check out the Patreon page or follow it on Twitter. The artwork is by graphic designer Kurt Woerpel whose work can at his website. The newsletter is copy-edited by Mariana Carvalho, with additional support from Taylor Curry. My personal website is davidturner.work. My current job is a Curation Analyst at SoundCloud, so all thoughts here represent me, not my employer. Any comments or concerns can be sent to pennyfractions@gmail.com.